Decanting wine for appearance's sake

I have taken to decanting my

wine of late. But this is not to improve its flavour; frankly, a lot of the

cheaper stuff dies a brief death in contact with the air. Nor is it to

reduce my consumption, although finishing an elegant demi-carafe seems to complete

a meal, and suppresses the urge to go and slump in front of the tv and polish

off the rest of the bottle.

No, the decanting is simply to avoid the suspicious glances of my household, as yet another garish bottle featuring animals of the world, flora, fauna, ugly graphics and strange typefaces threatens to grace the dining table.

Mrs K and I take great pride in the presentation of our dining table. I don’t go quite as far as one restaurant I visited before opening time, where a white-gloved maître d’ went around the tables matching every place setting, to the centimetre, against a photograph. (But I if I could…)

No, the decanting is simply to avoid the suspicious glances of my household, as yet another garish bottle featuring animals of the world, flora, fauna, ugly graphics and strange typefaces threatens to grace the dining table.

Mrs K and I take great pride in the presentation of our dining table. I don’t go quite as far as one restaurant I visited before opening time, where a white-gloved maître d’ went around the tables matching every place setting, to the centimetre, against a photograph. (But I if I could…)

We are not eating off crates.

Our dining table does not look like this. We take our Indian out of the foil

trays in which it arrives.

And if you do take care with

your choice and layout of crockery, cutlery, napery then surely you should be

concerned about the look of the wine bottle you put in the centre of the table?

I am not alone in this. That

great style icon Bryan Ferry, interviewed in the Wall Street Journal, objected to this label, which shows the rock that

makes up the vineyard’s terroir. “I hate that,” he said. You hate

the wine, asked the interviewer? “No, the label,” he said. “I can’t drink a

wine if it has an ugly label.”

This by way of comparison, is one of his

favourites. Bryan Ferry and I are as one. (Sorry, can I just have the

pleasure of repeating that sentence? "Bryan Ferry and I are as one…")

It’s been shown by lots of

controlled tastings that our judgment of a wine is influenced by things such as

cost, name, reputation and, of course, label. And why not? Like the plating up

of food, or the framing of a print, the presentation of something helps to

shape our experience.

Writing a while back about a

Chilean wine from the Lafite Rothschild stable, I explained why I believe that

actually, we do judge books by their covers; which is why we have Harry

Potter in adult jackets, and why the novels by one author will often be

redesigned to match the cover of his bestseller. So I get a little exercised

with critics who insist that we should ignore the label on a bottle of wine.

Appearances count.

One American wine website decided

to explore the alternative, that “it’s what’s inside that counts”. Just look at the hideous, garish bottles used to illustrate this

thesis.

Frankly, I wouldn’t care if

their contents were delicious. They look as if they contain fizzy

drinks. They would reduce my dining table to the status of a children’s party.

(Perhaps they include the

repellent Vimto, the only drink I know whose name is an anagram of its consequences.)

I could send you all over the

web to look at hideous wine bottles, but I will settle for just one, this set of

blue glass bottles with cartoon wine labels, the whole effect not only garish

and nauseating, but disturbingly childish on an adult drink.

I do have a couple of very

nice decanters, which are a pleasure to use and look at. But even before I did,

I have to admit that I would pour wine into anonymous bottles, rather than put

ugly specimens like these on my table.

(Here’s a tip – the Nicolas petites recoltes

range of vins de pays

come in completely clear glass bottles from which one can easily soak

the cheap paper labels. In the days before I could afford a decanter, I

used one

of these to serve wine anonymously. I was trying to follow the

minimalist

designer John Pawson, who had recommended this Baccarat crystal decanter – which

looks like a wine bottle, has the capacity of a wine bottle, will aerate your

wine no better than a wine bottle, but costs £238. The Nicolas bottle is

equally hopeless for aerating, of course [although the pouring from the

original bottle will help] but it only costs £5.49 – and yet unlike the

Baccarat one, it comes conveniently filled with wine…)

And a decanter will, of

course, genuinely improve some wines in flavour as well as appearance. I was

forced to put Cape Diversity's shiraz into a decanter, simply because of its

hideous label, depicting (Why? Why??) a species

of South African grass. Bryan Ferry would, I am sure, have agreed, although I

doubt he drinks much wine costing £6.95.

From the bottle, it was a

tight, unforgiving little wine. It left my mouth resembling a cat’s anus.

But decanted, and left a

while, the tannins softened, the wine opened up, and it became richer, softer

and altogether better than its price tag might suggest. Even Mrs K “thought it

was alright,” an approval rating neither its taste nor its appearance would

have been likely to achieve straight out of the bottle.

A decanter won’t solve

everything. And let’s face it, while you can decant a bottle of red, it’s a

little odd to decant your white (and harder to keep it cold), while only an

idiot would try and serve a sparkling wine decanted. (Put that Tesco Cava back, CJ…)

But at least it does keep your

wine anonymous, attractive and suitable for a civilised dining table. And while

a decanter can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, it can sometimes retrieve a

satisfying drink from a cat’s anus.

PK

Anglo-French name-calling – Les Rosbifs

And we, of course, similarly refer to the French as “Frogs”. My understanding is that they do not particularly like this term, although they probably prefer it to “cheese-eating surrender monkeys”.

However, there is a French winemaker who labels his wines Arrogant Frog. And there is clearly a belief that the way to make French wine appealing to a broader English market, and compete with the frank, in your face approach of some of the New World brands, is to have a jolly good laugh around clichés about the French, and the old Anglo-French entente cordiale. Or lack thereof.

So we have a whole string of wines which parade faux Frenchness, a case of the oafs meeting the oeufs. They play upon what might pass as French to the residents of Walford. You get wines like Les Dauphins, all tricked out with mock belle epoque designs. There was one at M&S called Chez Pierre which looked like the house wine of a French restaurant on Coronation Street. Clearly taking the St Michael.

Then we have French wines which play upon what is believed to be English tradition. Nonsense like 58 Guineas Claret, ignoring the fact that the French would never use the word ‘claret’ themselves.

And we have wines which take the mickey out of the French language, like Longue-dog, Goats Do Roam and Chat-en-oeuf. Which play upon Languedoc, Cotes du Rhone and Chateauneuf, respectively if not respectfully.

So perhaps it was only a matter of time before these absurd convolutions resulted in a French wine sold to the English by playing upon the way that the English are described by the French. And here it is, a Pays D’Oc red, Les Rosbifs.

Now personally, I don’t have a problem with us being described as “rosbifs”. It’s a hearty, red-blooded kind of a nickname. Better rosbifs than, say, coqs.

But of course, it doesn’t stop there. The label of Les Rosbifs is illustrated with what are presumably meant to to be English motifs. A knife and fork, for example, but crossed sideways, despite the fact that English children are taught not to do that. Some people say a crossed knife and fork indicates an argument to come, a superstition I seem to be proving correct.

There’s a hat on the label, which looks a bit like Tudor headgear and a bit like a crown. And there's what appears to be a bovine with a football, which might I suppose be a reference to Wayne Rooney.

What really rankles is the fact that this preposterous marketing construct has clearly not been created by the French themselves. On the back label, there is an explanation of the “good-natured” (sic) nickname “rosbifs”. It is said to be “an 18th Century gastronomic term describing our (my italics) distinctive style of cooking meats.” That’s “our” distinctive style, fellow Englishmen. Not “their” distinctive style – as it should be if written by a French winemaker.

Plus of course, there’s a further real giveaway. Obviously it is inauthentic for a French wine to put a stonking great varietal on its label. But worse than that; if this wine had an iota of French authenticity, they wouldn’t have called it Shiraz. It would be Syrah. Only, that word’s not as well-known in Walford…

In the end, what you’ve got underneath all of the flim-flam is a straightforward seven-quid Syrah. (I refuse to call a French wine Shiraz.) That rubbery smell like an old eraser…that initial clatter around your palate like a mouthful of marbles…that thick, velvety soupiness, settling down after the initial burn-off into a puddle of bitter cherries. Certainly not Bordeaux, the French wine which surely a traditional Englishman would choose.

Who on earth will buy this stuff? Do people really chuckle when they see it on a shelf, or laugh as they place it on their dining table, and point out the label to their guests? Is it cashing in on some kind of UKIP jingoism?

According to the official website, the classification Pays d’Oc IGP is “a unifying label, signifying quality, authenticity and imagination.” Far be it from me etc, but aren’t all three of those in question here?

PK

Artifice v Artisan – the two faces of one Rioja

It

is hard enough deciding which wine to buy. It is important to stand in

front of the shelves and appear suave and knowing, and not baffled by

the varieties and prices like a schoolboy faced with a complicated range

of condoms.

In general, I have think I have mastered the required image of sagacity. And then, I find myself faced with the situation I have captured here. On the left, we have Coto de Imaz Rioja, Reserva 2005. And on the right, Coto de Imaz Rioja, Reserva 2005.

In general, I have think I have mastered the required image of sagacity. And then, I find myself faced with the situation I have captured here. On the left, we have Coto de Imaz Rioja, Reserva 2005. And on the right, Coto de Imaz Rioja, Reserva 2005.

I think we can agree, without the intervention of forensics, that there are certain differences between these two adjacent bottles. An ordinary customer, their eyes fleeting nervously along the shelves, fearful of confusing the Rhine and the Rhone, might think these are two completely different wines. A wine-buff might anticipate some kind of arcane distinction, as between vintage and late-bottled vintage port. But no – they are exactly the same wine. They are both Coto de Imaz Rioja, Reserva 2005.

For ease of identification, let’s call them the one on the left, and the one on the right.

Someone, probably wearing challenging spectacles, has clearly told El Coto de Rioja that they need to rebrand. Their label needed to resemanticise its juxtapository elements to reengage the target cohort. Or somesuch.

Change the label! What, in time for the next vintage? No, right now. In the middle of a year? Just swap it over. No-one will ever see them together…

(There is probably some poor teenage shelf-stacker, still as confused at the order to put two visibly different bottles together on the shelves as I am to see them there.)

Now, people tell me that you’re not supposed to choose your wine on the basis of the label. I know that. But…what if you have no choice? If the same wine has two labels? You have to choose on the basis of the label.

Oh, it doesn’t matter, they’ll say. It’s the same wine. It doesn’t matter. Well clearly it does, otherwise they wouldn’t have changed it. It clearly matters to someone at El Coto de Rioja. And it matters to me. Because I don’t know which one to buy.

Are they really going to taste the same? The one on the left declares on the back that “long ageing in oak casks has provided this wine with great complexity and potential”, a clear and appealing statement.

But the one on the right says that “long maceraction (sic) times have provided it with a stable and powerful tannic structure. Its long ageing in American oak cask (sic again) has developed it to stand a long ageing in bottle and to assure a succesful evolution (all, sadly, sic).”

There’s something endearingly authentic about that clumsy translation, as if Manuel, prior to his job at Fawlty Towers, were working in the labelling department. “Is OK, Senor, I speak English well. I learn it from a book.

“I write label.”

And the one on the right just feels more genuine. The clumsy translation, the hand-drawn type, the shadowy woodcut…probably all similarly created in an earlier, Don Draper era of marketing, when it wasn’t the spectacles which were challenging but the tobacco consumption. But nevertheless, much more redolent of “el Siglo XVI” of which they boast on the label.

The one on the left is just knee-jerk upmarket, its polished look and language intended for the modern global market. The crisp edges and proper serifs of a digital typeface, the touches of gold foil (as opposed to gold-ish colour), the image of a winery where they have improved the weather, trimmed the shrubbery and shifted the boulders from the foreground.

It’s a shiny international construct, seemingly drawn from the design of cigarette packets.

Ironically, heritage and authenticity are some of the most desirable things in markets right now. The last thing most people want is to feel that a product has just been created, designed to chase the glossy money of oligarchs and oilmen, the banker’s bonus and the hedgie’s wedge. Artisan is a good word – artifice is not.

So waiting just around the corner will be another marketing chap, in his Carhartt jacket, Sunspel underwear and Woolrich shirt. And he’s going to say to Coto de Rioja, look at this wonderful old bottle I saw…it’s so authentic…

Of course, I bought the one on the right. I’m a sucker for authenticity. Even if it’s fake.

And what does it taste like? Well…the same as the one on the left.

PK

There are still

some of us, it seems, who aspire to some fantasy notion of Olde English

aristocracy. A “worlde” created by marketers, wherein we dine, attired

in our vestments, upon provender accompanied by trucklements. And, of

course, imbibing our libations. While we watch the telly.

The Georgians

were big on luxury claret. It was an 18th century signifier of wealth,

power and good taste. Might something of that, from a label like this,

rub off upon the 21st century? Let’s try it, thought “the biggest AOC wine group in France” After all, the only thing Georgian this market probably encounters in modern life is the Metropolitan Police.

And so, here it

all is – hogsheads, guineas, claret, George III coins, our first Prime

Minister and an old wine merchant, shovelled on to one label, with all

the historical inaccuracy a gullible public might swallow with their

wine. Oh, and untroubled by the idea that naming a wine with its price

is unspeakably vulgar.

Let us consider

this pseudo-Georgian world, in which we buy our claret by the hogshead.

This is a measure probably alien to Messrs Majestic, to whom a hogshead

is something you would buy from a butcher’s. But our wine is supplied from the substantial-looking premises of C Chevalier, Wine Merchant.

Judging by the architecture, and the customers, commercial success

clearly took the business well into the subsequent century.

Yet surprisingly, I couldn’t find a record of C Chevalier, Wine Merchant. Perhaps the business is now hiding its light under a bushel. Or a hogshead.

But its

substantial-looking building does however strangely resemble the

premises of one Call & Tuttle, Furnishing Goods and Merchant

Tailors, of Boston. There seems to be an extraordinary similarity, not

only in the architecture, but even in the clientele. It would be so easy

to confuse the two; I do hope there is no confusion about our handsome

order of claret.

Equally troubling is the version of history projected by the rest of this label.

“When

Britain made peace with France in 1713, claret was a pricey (and

fashionable) commodity, especially with the wealthy London set,” the label tells us. “One

such connoisseur was Sir Robert Walpole (First Lord of the Treasury at

the time) who used his contacts in the navy to smuggle in his favourite

clarets from France. It is said that he purchased up to twenty hogsheads

in a year to satisfy the British tastes for claret at a price of around

58 Guineas per hogshead.”

For one thing, “when Britain made peace with France in 1713”, with the Treaty of Utrecht, Queen Anne was on the throne – not George III, whose numismatically attractive coins are depicted on the label. George III wasn’t crowned until 1760.

And Sir Robert Walpole was not

“First Lord of the Treasury at the time”; he first gained that title in

1715, under George I, and properly in 1721. Never mind hogsheads, this

is hogwash.

Is there any connection between this claret and that which Walpole bought? The name, perhaps? Er, no – because, of course, the word claret does not exist in French, so they would never have put it on a label themselves.

And

surprisingly little is recorded about Walpole’s struggles with the

closure. “Your Majesty, I continue to be concerned about the South Sea

Trading Company, to say nothing of these wretched screwcaps which the

merchant Chevalier has put upon my claret…”

However,

Walpole did, at the peak of his career decades later, get through up to

20 hogsheads of claret a year. In the fascinating book, The Politics of Wine in Britain: A New Cultural History, Charles Ludington explains that “At the height of his power in 1733 [nb],

Walpole spent over £1,150 on wine, a sum that amounted to more than the

annual income of a prosperous country gentleman like his

father…Specifically, Walpole purchased seven hogsheads of Margaux, three

of Lafite, one of Haut Brion…Taken together, Walpole’s purchases of

luxury claret in 1733 amounted to approximately 234 bottles per month,

or nearly eight bottles per day.”

But much as I

would respect such an heroic level of drinking, Walpole did not

negotiate the Anglo-Austrian alliance under the personal influence of

eight bottles of claret. He hosted wine-fuelled political gatherings,

“little snug parties of thirty-odd”, at his Houghton Hall. I would

therefore draw attention to the difference between purchase and

consumption, as I’m sure Walpole had to do to his own spouse.

And would Sir

Robert, drinker of Margaux, Lafite and Haut Brion, have ordered

hogsheads of this blended contemporary brew for Houghton Hall? Hardly.

This is a light, easy-drinking Bordeaux, with a relatively bright nose,

thinnish in the mouth with a certain earthy quality. Oh, it’s drinkable,

but it’s not as interesting or special as it should be for £8.79. As if

it’s a good thing, they declare cheerfully at the end of their label

description that there is “No need to decant!”. No, none indeed.

There is, of

course, an issue as to how closely one might really wish to emulate that

“connoisseur”, Walpole. Swift was among those who criticised the

venality of his government, and of “upstart monied men” like him. Thanks

to his profligate lifestyle, Bob Booty, as he was lampooned, weighed 20

stone, and was described as “inelegant in his manners, loose in his

morals” by the Earl of Chesterfield.

But, Chesterfield also said that “He degraded himself by the vice of drinking.” Not all bad, then.

PK

PK

Double visions – the lookalike wine labels

When they said that drinking wine could leave you seeing double, this wasn't what I thought they meant.

I

would not wish you to think that I blunder along the shelves of my

supermarket blearily plucking in desperation at anything that reminds me

of a bottle of wine.

But

I have only the time it takes Mrs K to negotiate the bread and baking

aisles, during which I am left in the wine section, to choose the week’s

wine and to come up with a plausible story for purchasing it.

I’m looking for something that we really must have, we need to have, because of guests, or the weather, or something. And given the summer sun, what about that vinho verde

from Azevedo I read about, lovely for drinking on its own in the

garden. I recognise that tall bottle, that name, that label with an old

building on it. And there can’t be that many items in the aisle with

both ‘v’ and ‘z’ on their label, unless Sainsbury’s is now offering

vajazzles.

Well. Of course, I was proven wrong. It turns out that what I bought is not the lovely Quinta de Azevedo, described as "Almost bone dry ... thirst-quenching ...sparky, floral, stone fruit” - Jane MacQuitty. Not the Quinta de Azevedo described as “Filigree-light, dry white with pure, clean flavours of pear, apple and lemon, and a delicate hint of spritz” – Suzy Atkins. No, this is Torre

de Azevedo, described as “slightly syrupy, yellowish wine which

gradually reveals, as the chill wears off, a certain slimy fruitiness,

ending in an acidic attack to the throat like an onset of tonsilitis” –

Sediment.

More

fool me? Well sorry, but on a rushed morning in the supermarket, I

didn’t expect to need a wine encyclopedia. I know, you shouldn’t judge a

label by appearances, or a book by its cover – but if you see a book

cover that looks like the one you remember, and it says JK Rowling on

the spine, you’d be pretty copped off when you get home and realise it's

an adventure of the lesser wizard Harry Pooter.

And

this has happened to me before. Previously, in a short-lived

exploration of wine in a box. I made the mistake of thinking that Caja

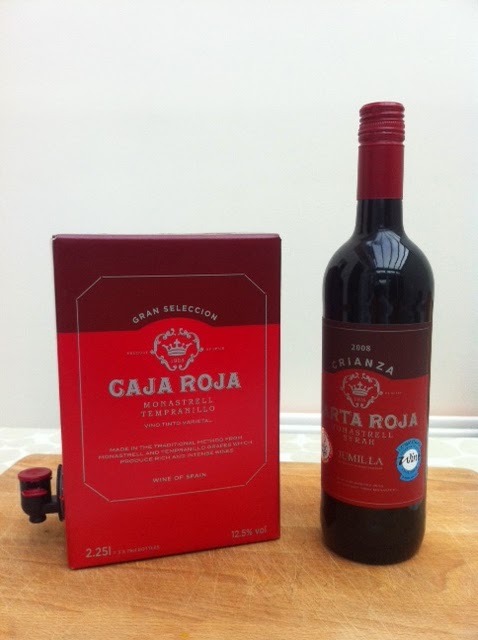

Roja, in a box, was the same as the similarly packaged Carta Roja, in a bottle. I submit, m’lud, that any harrassed shopper would assume these two are the same wine:

They are not.

Am

I the only person who is falling foul of this? The marketing people

worry about wine being baffling to the average consumer – and then set

them what amounts to a spot-the-difference test.

The

discount store Lidl, for example, is planning to target upmarket London

wine drinkers with some classy Bordeaux. ‘Lidl claret offensive’ said

one headline, a statement which I felt read more like a tasting note than a marketing strategy.

Lidl

will be selling, at £13.99, a wine from Chateau Siaurac, No, it’s not

Chateau Siaurac itself; nor is it the second wine of Siaurac, which is

Plaisir de Chateau Siaurac. But the ‘Reserve de la Baronne’ certainly

looks like them:

Perhaps you can pick it out from the Chateau Siaurac line-up:

So

before deciding whether a wine is the one you think it is, you have to

master some kind of identification parade. A general memory of a name

and a label, as I discovered, is no longer enough.

You

can’t just send someone down the road to buy a bottle of wine based on

your description of the label. “Oh, pick up a bottle of that red – it

has a white label with a sort of circular device in red, like a Celtic

symbol or something…” They might pass The Good Wine Shop, and bring back

the bottle of Clonakilla, which you meant – or they might pass Oddbins,

and bring back The Good Templar. Which you didn’t.

And

a little knowledge can sometimes be more misleading than useful. I

know, for example, of Chateau Ygay, a magnificent Rioja which I’ve

tasted but can’t afford. So a label with similar type practically leaps

at me from the Waitrose shelf:

The

distinctive swirly red lettering, the additional gold swirly

subtitle…could the significantly cheaper El Patito Feo perhaps be Ygay’s

second wine? Are they by any chance related?

No,

sadly not. El Patito Feo is not even a Rioja; it’s actually from a

different area of Spain. And while this upstart may be from the same

country, it is not in the same Liga as Ygay.

No

wonder people get taken in by fake wines, when it’s so easy to mistake

the real ones. Confused at first sight, it’s little wonder some of us

end up buying not quite the wine we thought.

Heaven forbid it could ever be a deliberate ploy…

PK

A crafty redesign – Banrock Station

I know why I used to drink it; it was to do with consistency. Well, there was an element of price in there as well, but let’s stick with consistency for now.

When you start drinking wine, consistency is one of the most important things; you want to know what you are going to get, without having to memorise a whole load of names, and varieties, and vintages. Only after a while was I able to move onwards and upwards, by filling my head with wine info as if I was cramming for some kind of exam. In fourteen hundred and ninety two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue; in nineteen hundred and eighty four, the Bordeaux vintage was piss poor…

Nowadays, I try to avert my gaze from the branded wines which crowd my supermarket’s shelves. It’s a little like trying not to look at something you know you really shouldn’t, like someone’s wardrobe malfunction, or television property programmes. But this time my eye was caught, by a new label (above) on the serried bottles of Banrock Station.

And you know what it’s like; whether you’re pushing a trolley, or driving your car up to a pedestrian crossing. Once your eye is caught, you just have to stop.

Back in the days when I did buy Banrock Station, it had a diamond-shaped label, a generically modern kind of design for a generically modern kind of wine. It even had a touch of gilt, which made me feel I was getting a little bit of class for my four quid or so:

Essentially, it kept quiet, perhaps not the best way to attract sales, but displaying a modesty which echoed the status of the wine and, frankly, sat comfortably on an equally modest table.

But look what has changed. Perhaps in an attempt to reflect their environmental, “good earth” credentials, they are attempting a rustic, craft kind of vibe. The paper is coarse and matt. The colour is earthy. And the printing is broken and flecked, as if attempting to suggest that the label has been crudely, artisanally stamped from a linocut or woodblock or something.

Now, there is a craft beer, The Kernel, whose label looks like crudely stamped brown paper. Once, it actually was crudely stamped brown paper; unable to afford properly printed labels, the brewer ordered a basic ink stamp, and handstamped the brown paper labels himself; the thick brown paper then stopped the bottles clanking together when he put them into boxes. Now, the production has hugely increased, and the labels are properly printed – but they still look like handstamped brown paper.

I’m also reminded of the live album Fillmore East, June 1971 by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, an official live recording which was printed to look like an illegal bootleg, with all of the authenticity such an album embodied.

Because in reality, Banrock Station arrives in industrial bulk. A back label (similarly framed in crude, broken lines) tells us that the bottle has been “filled” at “BS11 9FG”. This is the somewhat non-artisanal plant in Avonmouth, Bristol, where bulk-shipped wines arrive from Australia, and whose state-of-the-art bottling lines fill some 400 bottles a minute. Something tells me that this ruthlessly industrial process does not wait for someone to print each label individually from a carved potato.

There’s something here echoing the whole hipster authenticity thing. That uncomfortable conjunction of the appearance of craft with the world of modernity. These chaps who look like Canadian loggers, complete with plaid shirt, outback beard, stylishly weathered jeans and clumpy, half-laced boots. Oh, and a MacBook Air.

No-one, least of all a label designer, is going to make me think of Banrock Station as a small-batch, artisanal product. It never even was (unlike that craft beer). In fact it underlines its global reach by declaring on its label that it “contains sulphites, egg, milk” in no less than 19 languages. (Grapes don’t get a mention.)

And surely, the variations in taste and quality which occur from year to year in genuinely rustic wines would be anathema to a global, mass-market brand? Consistent wine for around a fiver, produced in huge quantity and delivered globally thanks to modern industrial processes. What’s to be embarrassed about?

But then, why do guys who code apps want to look like sharecroppers?

PK

A change of art

By way of contrast, what does this label say? It’s bright, it’s colourful, it’s lively, all positive attributes of certain kinds of wine. Perhaps pair it with colourful Tuscan crockery and maybe drink it from tumblers in a relaxed kind of way. Because “It’s ‘Bandol on a budget’, with softer edges.”

You’ve worked out where this is going, haven’t you? Of course; it’s the same wine. From the 2017 to the 2018 vintage, they’ve changed the label.

I got terribly exercised about this. I was upset, because I prefer the first label, which sits more comfortably on my table. Because I respect cool, austere design. Because that label looks sophisticated, which is how I like to see my wine, and now it looks loud, which is not. Because it’s now got yet another bloody animal on it.

(What is it about animals on wine labels? From birds and cats right down to frogs and penguins, you name them, you see them. There can only be a few genuinely unpleasant creatures left, which never appear on wine labels, because no-one has a good word to say about them. Like jellyfish. Oh.)

Anyway, I got even more exercised because, on a simple sales level, I could no longer see the bottle I wanted on the wine merchant’s shelf. I like to just pick up – or, in these awkward times, point at – the wine I want, in a knowledgeable, had-it-before manner. Instead of which I had to ask plaintively, “Oh, are you not stocking Talento any more?”, and then to feel ignorant because how was I to know they had changed the label?

I just wanted the same wine I had had before. And quite fundamentally, I don’t like change.. They say that a change is as good as a rest. Well, give it a rest.

But then, next morning, I thought about the way in which individual vintages change. The way in which, regardless of the (usually) consistent graphics of a wine’s label, the thing which really tells you about the character of a particular bottle may be the four little digits stating its year. That annual variation is celebrated by some wineries, as an aspect of their nature, a variation they proudly describe each year. (The only surprise being that it always seems to vary in a positive, purchase-encouraging way…)

So perhaps, if each year’s wine is genuinely different, the labels themselves should actually change each year? This is, after all, a new vintage (even if, to my palate, more like a boar than a bird). Perhaps the latest vintage deserves a new presentation, like the latest novel by an author, to show at a glance that it’s the same but different? Perhaps the misleading labels are the ones which don’t change, and suggest that the wine is essentially the same?

And then I got really philosophical, and wondered, can we ever drink the same wine twice? After all, a wine is constantly changing, not just from year to year, but even in the bottle. Even if the label is exactly the same, the bottle I opened last week is not the bottle I will drink tonight. Tomorrow’s wine must always be a little older, with a slightly different past. Like, indeed, ourselves. If Heraclitus had been having a picnic on the bank, before he considered whether he could ever step into the same river again, would he have stated instead that you can never drink the same wine twice?

Ah well. That’s what happens in lockdown, when you wake up early, and read Four Quartets outdoors, in a London profoundly quiet and still as you could never have imagined, while “Dawn points, and another day/Prepares for heat and silence.”

These days, eh?

PK

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.