...Caché

(2005): This wonderfully unsettling psychological thriller from

Michael Haneke, deconstructs the supercomfortable middle-class wolrd

of Daniel Auteuil, menaced by a hidden observer with a surveillance

camera. Terrible truths are, inevitably, revealed. Being a film about

well-heeled French domestic life - however threatened - it also

contains several eating and drinking moments, and some handsome red

wines: one of the absolute cornerstones of French culture, invisibly

corrupted, as it turns out, by the invisible presence of Auteuil's

stalker. That's how dreadful the threat is: even the innocent,

pleasurable, wine becomes a part of it. So what antidote can there be

to this existential terror?

Carry

On Up The Khyber

(1968): Best of the Carry

Ons

by a considerable margin, not least because of the celebrated

sequence at the end of the film in which Sid James, Joan Sims and

the rest, plough (with full decorations) through a formal British Raj

dinner, under heavy bombardment from an army of enraged tribesmen led

by the Khasi of Kalabar (Kenneth Williams) and his lieutenant,

Bungdit Din (Bernard Bresslaw). Bottles explode with shot, the

chandelier crashes from the ceiling onto the table centrepiece, the

orchestra is hit by a mortar shell, but the civilities never waver -

not least in the the consoling and civilising presence of fine wines,

a countervailing force against the dark barbarism outside. Clarets,

from the look of them. Lady Ruff-Diamond (Sims), picking a chunk of

ceiling from her pompadour hairstyle: 'Oh dear! I seem to have got a

little plastered!'

Bicycle

Thieves

(1948): But what if you

are the outsider? What if you are marginalised - like the father and

son in Vittorio de Sica's masterpiece? Wine becomes implicated in

your misfortune, an index, even, of your poverty and despair. Father

(Lamberto Maggiorani) treats son (Enzo Staiola) to a restaurant meal

with wine, a consolation for their latest round of misfortunes.

'Let's forget everything and get drunk!' he cries. But the next table

is occupied by a family of gallingly prosperous suburban Romans.

Their wine is plentiful and arrives in smart bottles with labels; the

father and son's comes in a greasy blank carafe. The father's good

mood begins to slip away. Within minutes, he is compulsively

rehashing the events that have led to his downfall - the theft of his

bike, mainly - and outlining the humiliation that threatens to

overwhelm them. The wine is a false friend, confirming the mood,

rather than banishing it. 'We'll find it,' says the son, braver than

his father, 'we'll go every day to the Porta Portese'. Do they get

drunk? No. But Dumbo does.

Dumbo

(1941): This is one which Disney himself had to finish off, when most

of his studio went on strike. It is also the one in which Dumbo and

his friend, Timothy Mouse, accidentally get soused on some leftover

grog - resulting in the authentically troubling Pink

Elephants On Parade

sequence. As anyone with children will tell you, this is one of the

hardest episodes in a cartoon film to explicate to a four-year-old -

harder, in its way, than the death of Bambi's mother or the

surprising uselessness of The

Jungle Book.

Its vertiginous transformations and distortions (multicoloured devil

elephants, amoebal ghost elephants) have something of the Little Nemo

cartoons, but without the charm; while the atmosphere of sick menace

is as bad as anything from Max Fleischer. This is not drink as we

know it. This is a trip to the pharmacopeia, and one which tells you

a lot about America's grimly conflicted relationship with drink and

self-loathing. Not entirely dispelled by

The

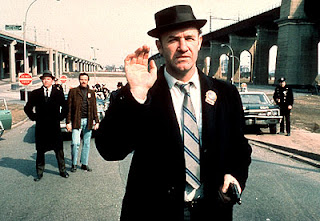

French Connection

(1971): Another great film: William Friedkin's best, Gene Hackman's

best, an unimprovable car chase, and a terrific stake-out sequence

with Popeye Doyle (Hackman) freezing his butt off as he watches bad

guy Charnier (Fernando Rey) tuck into a gourmet meal in a discreetly

sumptuous New York restaurant (actually the Copain). Hackman gnaws a

congealing pizza and blows on his chapped fingers; Rey luxuriates in,

yes, a fine wine, a wine whose very fineness indicates how terrible

and heartless he can be. This is wine as metaphor for evil - rather a

remorseless depiction, especially from the country which gave us Dean

Martin, but there you are. There is no necessary benevolence in the

drink after all - only the capacity to take on a moral colour from

whatever its surroundings happen to be. Which leads us handily back

to the bottle on the sleek Parisan

dining

table...

CJ

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.